Pacifica in 1939: San Francisco's Own Version of World's Fair Art Deco

By Glenn Loney

Early in 1939, Americans were very much aware that a major world's fair would be opening soon in New York City. National magazines carried stories about the rush to finish the buildings on schedule. Pictures of the rising needle of the Trylon and its structural escort, the Perisphere, were widely reproduced. On the eastern seaboard, fair fever was steadily mounting. All advance reports on the stunning new buildings, the innovative styles, and the futuristic designs for major displays suggested an unforgettable experience. And for those lucky enough to see the New York World's Fair, in those dark days of the Great Depression, it has remained memorable.

On the West Coast, however, few people could afford the trip east.

But that was not the main reason for creating what was officially known as the Golden Gate International Exposition. On one level, the Depression itself was an impetus, since the fair's organizers were convinced that building and operating such a large-scale show would provide many jobs and bring thousands of tourist dollars into the coffers of Bay Area businesses. On a slightly higher level of local self-interest was the idea that the fair would attract new industry, new investments, and new workers, not only to San Francisco, but to California––and the West as a whole––so the western states could show their talents, wares and resources to the world.

The real spur for an exhibition of international scale was, however, the projected completion of what was to be the longest suspension span in the world: the Golden Gate Bridge, and its immediate predecessor, the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge. As construction proceeded on these multimillion-dollar, simple but elegant Art Deco structures, mud was being dredged from the Bay to build up the shoals off the mid-Bay island of Yerba Buena into an international airport, catering to the Pan American Clippers bound for Asia.

San Franciscans, expedient and resourceful since the Gold Rush and through the disastrous 1906 earthquake and fire, saw a second use for the new airport. Christened "Treasure Island," it could also provide an excellent site for a world's fair. The two huge Clipper hangars could serve as exhibit halls until the fair closed. A permanent administration building would also be constructed; all these would be designed in a no-nonsense 1930s style. Something more special had to be found for the architectural theme of the ephemeral fair.

The romance of the China Clippers, the attraction of exotic cultures across the ocean in Asia and Oceania, the recent discovery of the color and excitement of Latin America, all pointed toward the theme. The airplane would soon link all the nations bordering the Pacific Ocean in a matter of hours, if not days. Ships sailing from San Francisco were already doing that, but it took weeks or even months. Thanks to Pan American planes and some ingenious punditry, the Pacific was perceived as some kind of big lake––or puddle, to the irreverent––around which all the communities ought to be friends, linked in trade and cultural exchange. And so, the concept of the "Pacific Basin" became popular.

It wasn't a bad idea then, and it isn’t now––though Seattle is currently the city that sees itself as the key American city on that basin.

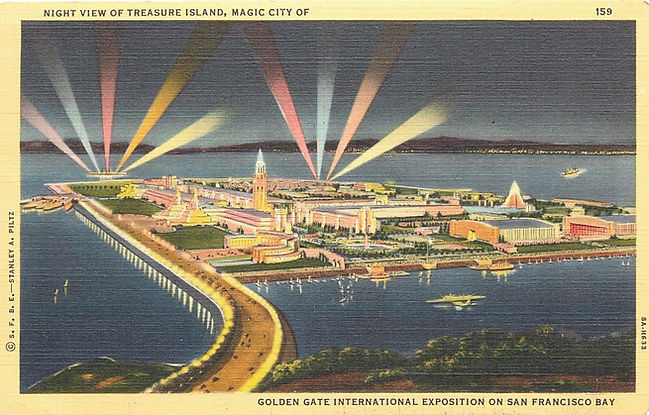

Unfortunately for the plans of Pan Am and the dreams of the exposition's promoters, on Sunday, December 7, 1941––a date that President Franklin D. Roosevelt said would live in infamy––the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. That put a halt to peacetime Clipper traffic, not to mention trade and cultural exchanges with Asians on the other side of that big Pacific “lake.” Treasure Island, the momentary lath-and-plaster jewel that by night had gleamed in a rainbow of pastel lights during its 1939 and 1940 seasons, rapidly became a U.S. Navy base.

The incredible Art Deco confections, so hastily built for the two years of celebration, were even more rapidly wrecked, replaced by long rows of regulation Navy barracks. The hangars and the harbor facilities on the island proved invaluable as the Navy prepared to send thousands of young men out into the Pacific Basin. Sadly, a number never returned.

Nor did Treasure Island return to civilian use as an airport. Owing to the nearness of the towers and spans of the two great bridges, it was not ideally sited anyway.1

But when the Golden Gate International Exposition opened on February 18––the same date the 1915 Panama Pacific Exposition threw open its gates to San Franciscans and visitors, newspapers and magazines, at least on the West Coast, couldn't find enough superlatives to describe the wonder of the architectural vision and its glories.

In 1939, it seemed an extraordinary vision of a streamlined future, not only in buildings, landscaping and lighting effects, but also in the way we would henceforth live our previously depressed and economically blighted lives. I know; I was there, ten years old, it's true, but eager to take it all in. I'd seen pictures of the Panama-Pacific, with its fantastic excesses of stucco ornament: Victoriana, masquerading as High Renaissance, Baroque, Rococo, and Neo-Neronic. All that had survived of that enchantment was Bernard Maybeck's chastely classic Beaux Arts Palace of Fine Arts. And by that time, its lath-work and plaster were already rotting away. (Years later, it would be replaced in concrete at immense cost. Would that someone had done that for some of the 1939 Exposition!)

Even at the age of ten––with no previous exposure to any sort of arts experience, as we lived on a mortgaged, unprofitable farm––I was puzzled by the style, which the fair's architects were pleased to call "Pacifica." In its verticalities, its squares, circles, cubes, and spheres, it suggested some futuristic geometry. Thin lines of color or molding gave chunky, windowless exhibition halls a streamlined feeling, hurrying the crowds along to take in as many exhibits as possible in a day.

At the same time, there were echoes of the past, of Beaux Arts and lost civilizations. In keeping with the Pacific Basin theme, architectural and decorative elements from Asia had been abstracted, to be wedded with those of the Aztec, Toltec, Maya, Inca, and even California Gold Rush rustic and Hispanic hacienda styles. At the time, I loved it all. Looking back, I recognize with shock, the amount of schlock, especially in the profusion of fountains and allegorical statues, surely a holdover from 1915.

Today, I can understand why this was. Arthur Brown, Jr., was the chief of the architectural commission that designed the fair and supervised the individual sculptors, muralists, painters, and lighting designers. Brown was also the architect of the Beaux Arts San Francisco War Memorial Opera House, working on that with G. Albert Lansburgh, who designed the Golden Gate and the Warfield Theatres––not to mention New York’s Martin Beck (now the Al Hirschfeld) Theatre. Brown's sympathies were with the past, not with the future.

Perhaps the cleverest critique of this world's fair's architecture was made by Richard Reinhardt, in Treasure Island, 1939-1940: "Borrowed from Malaya, Indonesia, and the ancient jungle cities of Cambodia and Yucatan, the architectural style of Treasure Island was a peculiar product of its times. Arthur Brown, Jr.'s committee of mellow, sixtyish Beaux Arts architects vowed to avoid the influence of contemporary fashion. Ignoring new materials and organic form, they invented a unique syncretistic style that had no past and no future. But history played them an ironic trick; with its laid-on grandeur and its nostalgia for traditional decoration, Pacific Basin style resembled the 1930s fascist architecture of Mussolini's Italy and Hitler's Germany."

That's Reinhardt's fortuitous hindsight, of course, but he's seldom off the mark in his nostalgic evocations of that wonderful fair, nor are his considered judgments of its merits unfair. But why not let Brown and his crew speak for themselves?

In the Official Guide Book (25¢ then; around $10 now, if you can find a copy), they explained what they sought in an article titled "A New Style of Architecture/Designed by Californians.” In their considered opinion, "An important requirement for a great Exposition is a new type of architecture, a style that will herald building design of the future or a style that will harmonize with its surrounding environment. The Golden Gate International Exposition Architectural Commission was equal to this requirement, and as a result, the new mode, 'Pacifica,' was created to embody building motifs from both the eastern and western shores of the Pacific..."

In addition to Brown, the commission included Lewis P. Hobart, William G. Merchant, Ernest E. Weihe, and Timothy L. Pflueger, whose Federal Building, with its impressive courtyard colonnade of steel beams, was much admired as a harbinger of future federal designs.

The northern part of the Treasure Island landfill was soggy and would continue to settle. It was reserved for parking. Cars drove off Bay Bridge ramps, around Yerba Buena Island, and onto Treasure Island on the edge facing San Francisco's skyline. The road to the parking lots ran in front of a huge wall. The fair was, for effect, a walled city––without a back wall. The dominant image, seen from afar, was the central Tower of the Sun, an Art Deco cinema palace fantasy topped with a golden Art Deco phoenix, symbol of San Francisco's rebirth from the ashes. Close up, however, the most memorable architectural and decorative features of the entire fair were the "Elephant Towers," immense cubistic pachyderms, atop stepped pyramids. They, their attached wall expanses, and the ingenious wind baffles between them, all constituted a Great Wall that instantly encompassed both past and future.

In my youthful vision they certainly did that, and in the view of many other people as well. Ernest Weihe designed the wind baffles, set between the two elephantine entrance guardians, to continue the illusion of a wall, at the same time permitting visitors to enter through the unseen spaces between panels. These were set off by great metal poles with lighting high atop them, concealed under cylindrical, futuristic shades.

Each court of the fair had distinctive lighting towers, appropriate to its theme. The 1,000-foot-long Court of the Seven Seas, leading down from Ralph Stackpole's monumental statue of Pacifica, had crow's nest lamp poles. Pacifica looked like a modified Mayan sculpture––or a Picasso cubist portrait in 3-D.

Behind Pacifica, there was a metallic curtain of stars, and behind that, were a series of colored lights that steadily ran through its changes at night. And behind that was a wonderful show, The Cavalcade of the Golden West, complete with two real-life Gold Rush locomotives to chug in from stage right and stage left on real tracks as a cast of hundreds drove the Golden Spike at Promontory, Utah, linking the nation by rail in 1869.

There was also a volcano that erupted, and this was long before Mount St. Helens. Mounts Lassen or Shasta were its inspiration. But this rustic reminder of the Old West was balanced by the Art Deco elegance of sculptures and reliefs by Jacques Schnier and others.

The Elephant Towers looked as though they'd stand forever. They were the creation of a 26-year-old designer, Donald Macky. Richard Reinhardt notes that some critics suggested they were just giant versions of Chinese wood block puzzles. As it turned out, wood they certainly were: Douglas fir planks nailed on frames, with a coating of pink stucco. The fair Guide Book was especially proud of the composition of that stucco, by the way. It notes that it had been mixed with Vermiculite, a remarkable man-made substance that caused walls coated with it to glow like a thousand jewels.

From the Guide Book, there is this comment about the Towers: “To avoid the effect of too great masses, the west elevation is broken by the Northwest Passage, leading to the Court of Pacifica, and the Portals of the Pacific, leading to the Court of Honor. The ramparts of the main portals are spread in the heavy masses of stepped pyramids, which converge sharply into towers supported by formalized elephants and climaxed by elephant heads and howdahs, emphasizing the [Asian] theme.

“The huge, windowless exhibit palaces, 100 feet high, give the effect of an ancient walled city, and the interior courts, with long rows of square pilasters, are reminiscent of Angkor Wat. Mingling Oriental, Cambodian, and Mayan styles in the lesser masses and details, an effect of basic beauty, refinement, and richness is interwoven with a mystical touch of yesterday...."

Well, that's what they thought they were doing, breathtaking, and, as I've said, I wasn't alone in that. But, in addition to these thematic monuments, which were said to have cost almost $7 million to build, there were the astonishing exhibits inside. (It should be remembered a double room in a hotel then started at $2.50, so one could build a lot for a few million, especially if the structure were twentieth century Potemkin sham.) Among the special treats was seeing oneself on primitive television, or watching the Westinghouse tin robot smoke a cigarette and talk to us. There was a see-through plastic Packard, and a clear plastic telephone as well.

Knowing where the Hormone Woman––you could also see into her––and the only escalator on the fairgrounds were located helped me win season's tickets in an Oakland Tribune contest. At ten, I discovered you could have three meals a day by making the rounds of the exhibits in the Foods and Beverages Building. How about a lunch of Del Monte tomato juice, Kraft Cheese, and Ritz Crackers, topped off with Diamond Walnuts?

The fair courtyards echoed to recorded and live gamelan and marimba music. Various Latin American and South Asian lands had built traditional and distinctive pavilions. There were some odd groupings: The Life History of the Redwoods was near French Indochina. Only France, Norway, and Italy represented all of Europe. The rest were in New York in the Shadow of the Trylon and the Perisphere. Soon, both France and Norway would be victims of Blitzkrieg by Italy's ally, Nazi Germany. What an innocent prelude both fairs were to be to the 1940s decade of carnage.

All Postcards and map: From the collection of an ADSNY member

Note: This article was originally published in the March--June 1982, Volume 2, Number 2, edition of the Art Deco Society of New York News.

Endnote:

1 It was closed as a naval base in 1997 and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Article originally published in the Art Deco New York journal, Vol. 4, Issue 1, Winter 2019. View a digital version of the full journal here.