From Skyscrapers to Silks

The Jazz Age: American Style in the 1920s

By Sarah D. Coffin & Emily M. Orr

In the 1920s, boundaries between the industrial and the domestic—as well as the urban exterior and the private interior—were shifting and even dissolving, therefore vastly influencing the realm of design. Designers drew upon the skyscraper and its dominant profile in the urban exterior landscape for their products for the interior. At the same time, the mechanization of industry and the speed of transportation systems inspired new forms that infiltrated everyday life inside the home. In addition, the private sphere of the modern apartment was increasingly on view for public consumption in shop windows and museum and department store exhibitions, as well as in the pages of magazines.

Textiles, for use in the domestic interior and for fashion, provided a canvas for the depiction of the energy of the urban exterior. For instance, Ruth Reeves’s Manhattan pattern, designed as a wall hanging for use in “city offices, apartment foyers,

(Fig.1) Installation view of The Jazz Age: American Style in the 1920s.

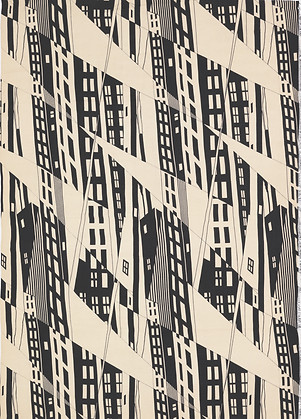

hotels, restaurants and clubs,” presented a Cubist collage of the sights and sounds of the city: skyscrapers, automobiles, factories, the Statue of Liberty, the Brooklyn Bridge, and office workers.1 The New York department store W. & J. Sloane suggested, “the ‘office’ of a country house, where necessary communication with the city is maintained, would seem to demand this design.”2 From 1925 to 1927, Stehli Silks Corporation engaged contemporary artists to produce a collection of “Americana Prints” that incorporated “the skyscraper, jazz, and other modern notes of energetic America.”3 The author and illustrator Clayton Knight’s dress fabric, Manhattan, the most successful design of the series, showed the city skyline in a segmented vertical composition (fig. 2).

Particularly as America’s commodities market struggled under the pressure of the Great Depression, consumers desired to invest in products that offered a futuristic, optimistic outlook that represented a break from earlier design. In a 1928 monograph on industrial art for the Metropolitan Museum of Art entitled Art in Merchandise: Notes in the Relationships of Stores and Museums, the museum’s president, Robert W. de Forest, wrote, “What I would particularly emphasize at this time are the significant evidences that the America of huge factories and of mass production is beginning to harness the attractive force of good design in team with the tractive power of her machinery.”4 The machine-made symbolized progress and machine forms increasingly influenced domestic products. Items for decorating, dining and serving, shown off when entertaining guests, were particular targets for this new aesthetic. Bookends took the shape of cogwheels. Charles Lindbergh’s Spirit of St. Louis decorated wallpaper (fig. 3) and perfume bottles, and automotive styling influenced everything from graphic design to jewelry. Walter Dorwin Teague’s Lens Bowl for Steuben used the same molds that were already in use for the railroad signal lights that Steuben produced.5 The bowl’s concentric circles, originally designed to disperse light, were equally striking for their pronounced geometry that evinced their mass-produced quality (fig. 4). The streamlined appearance of trains, planes and cars impacted the design of products, cleverly seen in a cocktail shaker and traveling bar in the shape of a dirigible by J.A. Henckels (fig. 5).

(Fig.2) Textile, Americana Print: Manhattan, 1925

(Fig.3) Sidewall, The Lindbergh, 1927

(Fig.4) Lens Bowl, 1932

(Fig.5) Zeppelin Airship Cocktail Shaker and Traveling Bar, 1928

Designers harnessed materials such as plate glass, tubular steel, and iron, largely associated with the realms of architecture, the factory, and wartime production, to great effect for furniture and decorative accessories, offering new possibilities for the domestic interior. The French designer Edgar Brandt spurred a revival of interest in interior furnishings made of iron in the 1920s. Brandt opened his own gallery in Paris, as well as a showroom in New York, called Ferrobrandt, which was in business from 1925 to the fall of 1927. The Brandt workshops made decorative radiator covers, lamps, firescreens, console tables, mirror frames and more. Agnes Milles Carpenter, a New York apartment dweller with modern taste, saw Brandt’s ironwork in Paris at the 1925 Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes. A year later she commissioned Brandt’s partner, Jules Bouy, to design a dining room that included a wrought iron table base in the latest style she had seen there. In fact, according to an article in Good Furniture Magazine of Furnishing and Decoration, wrought iron was to be used not only for all the furniture, but for “the window draping as well.” (fig. 6). The magazine deemed Carpenter “probably the first of American connoisseurs to appreciate the new possibilities of wrought iron as a decorative fitment.”6

This modern interior, fitted out for example with fabrics of urban motifs, ironwork accents and streamlined tableware was increasingly on public view as room settings drove the organization of exhibitions at Lord & Taylor and R. H. Macy & Co. as well as the Metropolitan Museum of Art. These arrangements encouraged consumers to imagine how the curated interior might fit within their own lifestyles. The department store show window was also an important exhibition space for modern design. Donald Deskey’s windows for the New York department store Franklin Simon frequently featured folding screens as backdrops, an element often used in his domestic interior designs.7 Deskey’s window displays were notable for their mixing of materials such as cork, metal, and corrugated steel (fig. 7). This approach of assemblage, along with the use of screens, extended into his interiors; for Adam Gimbel, president of Saks Fifth Avenue, Deskey designed an apartment, one room of which had cork walls, a copper ceiling, linoleum floor, pigskin chairs, and metal trim.

(Fig.6) Drawing, Dining Room Wall Elevation, Agnes Miles Carpenter Residence, 950 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY, 1926

(Fig.7) Drawing, Design for Window Display, Saks Fifth Avenue, New York, NY, c. 1927–28

This modern interior, fitted out for example with fabrics of urban motifs, ironwork accents and streamlined tableware was increasingly on public view as room settings drove the organization of exhibitions at Lord & Taylor and R. H. Macy & Co. as well as the Metropolitan Museum of Art. These arrangements encouraged consumers to imagine how the curated interior might fit within their own lifestyles. The department store show window was also an important exhibition space for modern design. Donald Deskey’s windows for the New York department store Franklin Simon frequently featured folding screens as backdrops, an element often used in his domestic interior designs.7 Deskey’s window displays were notable for their mixing of materials such as cork, metal, and corrugated steel (fig. 7). This approach of assemblage, along with the use of screens, extended into his interiors; for Adam Gimbel, president of Saks Fifth Avenue, Deskey designed an apartment, one room of which had cork walls, a copper ceiling, linoleum floor, pigskin chairs, and metal trim.

Donald Deskey’s work for Gimbel led the latter to introduce Deskey to Paul Frankl, the Austrian-born designer who moved to the United States in 1914, and whose New York gallery was becoming increasingly associated with an original modern American style. While Deskey had studied in Paris, returning in 1925 to see the Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes with other American designers, such as Gilbert Rohde, Frankl chose to stay in the United States during the Paris fair, initiating his experimentation with skyscraper forms that led him to create the first Skyscraper furniture bookcases that started as variations on stacked wood boxes, first appearing in 1926 (shown in fig. 1). Shortly thereafter came Gimbel’s introduction, and Frankl invited Deskey to create screens and other decorative objects to sell at his gallery. Deskey’s love of screens started when he was in Paris, where he saw and created screens as space dividers, both as decorative and architecturally relevant elements to the new adaptive spaces in modern interiors. Deskey had seen and admired the reflective surfaces of Jean Dunand’s lacquerwork screens and found new materials to emulate these. However, it may have been Frankl’s influence that started Deskey’s use of a stepped profile for his screen acquired by Glendon and Louise Allvine for their Long Island home, and a possible mate to it, with steps that run in the reverse direction (fig. 8). It may be that the metallic surfaces that Deskey created spurred Frankl in a similar direction. Frankl’s earlier furniture was in natural and stained wood that appealed to producers such as the Grand Rapids Furniture Company; but after their meeting, he too included vibrantly painted and reflective surfaces for his furniture.

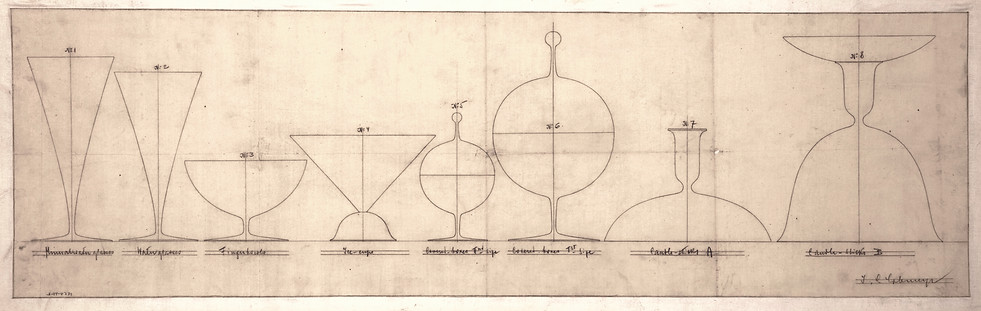

This is just one of the many interactions of American designers with their European trained counterparts that led to a new American style. Most of these émigré designers came from the Austro-Hungarian Empire or Germany and sought opportunities in more robust economies, such as the United States. Some also found a way to work with Americans through the 1925 Paris Exposition, where the confluence of taste, patronage, artistic revolutions, and style, led Americans to be introduced to wares from these countries. Agnes Carpenter, who commissioned the ironwork dining room from Jules Bouy, also saw the work of Viennese glassmaker J&L Lobmeyr, who had a selection of work at the 1925 Paris Exposition. As a result of seeing designs from the Ambassador service designed by Oswald Haerdtl, she commissioned from Lobmeyr a whole suite of drinking glasses, bowls, plates and specialty pieces, such as bonbonnières and display pieces, all in very thin muslin glass with geometric forms, for her New York apartment. The drawings sent for her approval and company records indicate that this work was carried out in 1926 (fig. 9).

This cross-fertilization of French avant-garde artistic movements with Austro-Hungarian and German design training, and the American interest in industrial design and mass production methods, along with the home-grown skyscraper for impact, led to a powerful American contribution to design in the 1920s. During the Great Depression production methods made modern design not only available but compelling in times of economic hardship. This is one of the many narratives that run throughout The Jazz Age: American Style in the 1920s.

(Fig.8) Screen, c. 1928; Designed by Donald Deskey

(American, 1894-1989)

(Fig.9) Drawing, Designs for Drinking Vessels, Covered Dishes, Candle Holders, c. 1926

About the Authors:

Sarah D. Coffin is the curator and head of the Product Design and Decorative Arts Department and Emily M. Orr is the Assistant Curator of Modern and Contemporary American Design at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum.

All photos: Matt Flynn © Smithsonian Institution

Endnotes

(1) Exhibition of Contemporary Textiles: December 1930, exh. cat. (New York: W. & J. Sloane, 1930), n.p.

(2) Ibid.

(3) “Artists Localize Our Silk Designs,” New York Times, November 1, 1925.

(4) Robert W. De Forest, Art in Merchandise: Notes in the Relationships of Stores and Museums (New York: The Gilliss Press, 1928), 1.

(5) Diane C. Wright, entry for “Lens Bowl,” in John Stuart Gordon, A Modern World (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2011), 190–191.

(6) Howell S. Cresswell, “New Ideas in Decorative Wrought Iron,” Good Furniture, February 1927, 70–71.

(7) Michael Komanecky, “The Screens and Screen Designs of Donald Deskey,” Antiques, May 1987, 1066.

Full Image Captions

(1) Installation view of The Jazz Age: American Style in the 1920s.

(2) Textile, Americana Print: Manhattan, 1925; Designed by Clayton Knight (American, 1891 - 1969); Manufactured by Stehli Silk Corporation (New York, New York, USA); Silk, printed by engraved roller; 71.1 × 52 cm (28 × 20 1/2 in.); Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, Gift of Marian Hague, 1937-1-4.

(3) Sidewall, The Lindbergh, 1927; Made by United Wallpaper Factories, Inc. (Chicago, Illinois, USA); Machine printed with engraved rollers; 115.7 x 76.2 cm (45 9/16 x 30 in.); Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, Gift of Grace Lincoln Temple, 1938-62-54.

(4) Lens Bowl, 1932; Designed by Walter Dorwin Teague (American, 1883–1960); Form patented by Charles F. Houghton (American, 1846–1897); Manufactured by Steuben Glass Works (Corning, New York); Mold-blown glass; 34.9 × 10.2 cm (13 3/4 in. × 4 in.); Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, Promised gift of George R. Kravis II.

(5) Zeppelin Airship Cocktail Shaker and Traveling Bar, 1928; Manufactured by J. A. Henckels Twin Works (Solingen, Germany); Silver-plated brass; 30.5 × 10.2 × 8.3 cm (12 in. × 4 in. × 3 1/4 in.); Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, Promised gift of George R. Kravis II.

(6) Drawing, Dining Room Wall Elevation, Agnes Miles Carpenter Residence, 950 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY, 1926; Designed by Jules Bouy (French, 1872–1937) for Agnes Miles Carpenter (American, d. 1958); Graphite, blue crayon on tracing paper; 35.9 x 52.4 cm (14 1/8 x 20 5/8 in.); Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, Gift of the Estate of Agnes M. Carpenter, 1958-133-2.

(7) Drawing, Design for Window Display, Saks Fifth Avenue, New York, NY, c. 1927–28; Designed by Donald Deskey (American, 1894–1989); Brush and silver paint, watercolor, pastel, graphite on off-white illustration board, ruled borders in graphite; 38.1 x 50.7 cm (15 x 19 15/16 in.); Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, Gift of Donald Deskey, 1975-11-65.

(8) Screen, c. 1928; Designed by Donald Deskey (American, 1894-1989); Silver leaf, lacquered wood, cast metal (hinges); Right Panel: 198.1 × 46.4 cm (6 ft. 6 in. × 18 1/4 in.); Center Panel: 168.3 × 61 cm (5 ft. 6 1/4 in. × 24 in.); Left Panel: 153 × 46.4 cm (60 1/4 × 18 1/4 in.); Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, Promised gift of George R. Kravis II.

(9) Drawing, Designs for Drinking Vessels, Covered Dishes, Candle Holders, c. 1926; Designed by Oswald Haerdtl (Austrian, 1899–1959); Manufactured by J. & L. Lobmeyr (Vienna, Austria); Graphite on tracing paper, lined; 29.2 x 99.1 cm (11 ½ x 39 in.); Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum; Gift of Frederick G. Weisser, 1958-77-2; Photo: Matt Flynn © Smithsonian Institution.

Article originally published in the Art Deco New York journal, Vol. 2, Issue 1, Spring 2017. View a digital version of the full journal here.